This year's deadline is

September 30. We will award the Tom Howard Prize of $1,500 for a poem

in any style or genre, and the Margaret Reid Prize of $1,500 for a poem

that rhymes or has a traditional style. Ten Honorable Mentions will

receive $100 each (any style). The top 12 entries will be published

online. The top two winners will also receive one-year gift

certificates from our new co-sponsor, Duotrope.

The entry fee is $12 per poem.

As final judge of the Contest,

I was tasked with selecting two winning poems—one in each category—and

ten Honorable Mentions. I failed.

It's not that I didn't read

each poem assigned to me from among 2017's 3,223 submissions. I did.

It's not that I didn't reread them. Over the course of several months,

I did. And it's not that the poems were too similar; that none of them

stood out. Indeed, it was their dissimilarity that undid me. For how to

choose, when the comparison is not apples to apples but apples to a

Hesco fence, a short bibliography of secrets, or the Towers of Silence

where the dead of the Parsi tribe wait?

"Unshorn, we are death

itself: serpentine / and secret. Our hair conceals our power / to bear

souls into the world, to feed them / from our own flesh: sower, tender,

reaper, / shepherd, wolf, wool and fur." These poems incited me.

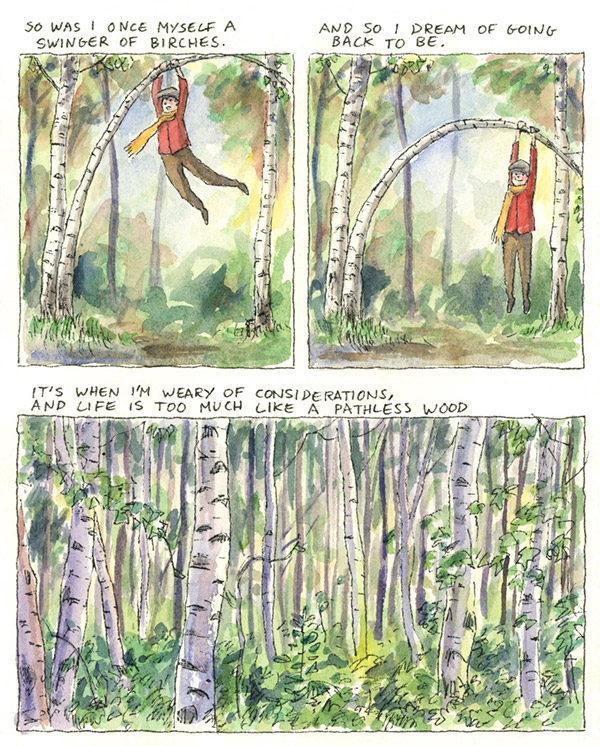

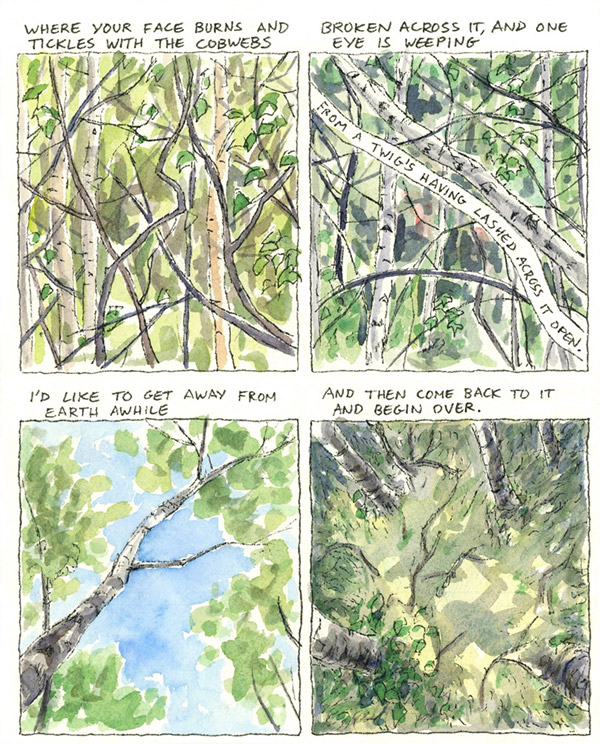

"...Birds practice ascending declensions / of birdsong: Amo; Amas;

Amat..." These poems lulled me. "Gradually words scattered,

fled their posts, / dictionaries, unread, lay open on his desk."

These poems wracked me. "When you put Saturn in the bath / it

floats. / It's true." These poems schooled me. There were too many

standouts.

Winding through the Bay Area's

redwood forests with my daughter, then, I noted which poems tracked and

followed me. Teaching a class of MFA students, I considered which poems

I might've used as examples of impeccable this or explosive that. And

in bed, tossing and turning, I acknowledged which poems leveraged

words, strategies, motifs, cadences I wished I'd come up with first.

Ultimately, I settled upon fifteen poems—and Winning Writers was

gracious enough to green-light the additional honorable mentions,

because...well, read on and discover exactly why.

The Winners

"A

Word Like Rat" by Karen Harryman

Tom

Howard Prize for verse in any style

Each of us is, or has been, gripped by a secret; shaped and crushed by

a secret. "A Word Like Rat" begs for turnaround: for secrets

we can hold, shape, crush, and a word that compresses them further,

till they're manageable. This dexterous poem ambushed me. First, I was

meeting Aunt Sandra—a commanding woman, even in her housecoat—as though

the speaker and I were childhood friends. In the space of a few lines,

years went by. And I found myself face to face with the speaker again,

sipping coffee. Concerned. But my experience of the poem didn't end in

that cafe. Nor in this one, where I compose my remarks. For this poem

is a blank, a puddle. As much as it contains the dirt—the speaker's

distress in the wake of her father's solitary death—it also reflects

the sky, and within that sky all our rising prayers for control over

the uncontrollable.

"From

the Mouth of Kitsee's Inlet" by A.T. Hincapie

Margaret

Reid Prize for verse that rhymes or has a traditional style

This loose corona of American sonnets is no outdated artifact.

"From the Mouth of Kitsee's Inlet" is as bold and modern a

crown as any you might admire on a drag queen strutting the stage.

Expertly forged from convention and rebellion, burnished to perfection

through exacting revision, it stands up to scrutiny. If each individual

poem in this crown of sonnets is autonomous, so, too, are the precise monostichs,

couplets and tercets—every image, every argument and observation, every

thematic concern bearing the glint of brilliance. A young nephew buries

fish bones at the mouth of the empty inlet, "for next year's

fish". An elderly mother hoards barrels of five-minute greenhouse

gutter floods "for next year's food". We gather our

obsessions, petal by petal, into our hungry mouths. "Now becomes

nonverbal" so that we do not converse with these poems, but graze

against them; run a finger along the crown's cool surface, circling

smoothly from the first poem's opening word to the last poem's final

word: "Look."

While this poem overturns

multiple conventions, it pays strict homage to others. Traditional

elements span both form and content: for example, each sonnet's closing

couplets deliver a volta—or "turn"—whereby the argument or

mood of the poem pivots, displaying the complexity of timeless issues

such as mortality, obsession, and the unassailable passage of time

(both seasonal and personal). To add flavor to this thematic

profundity, the poet sprinkles in time-honored ingredients including

laments, philosophical musings and explicit, time-honored

references—e.g., to the tale of Icarus.

The most notable tradition

upheld by "Kitsee's Inlet", though, may be the formal

repetition that melds these artful sonnets into a crown. In a

traditional corona of sonnets, the final line of the preceding poem is

repeated as the first line of the succeeding poem: here, echoing

words link each poem's last line with the first line of the poem that

follows. Moreover, in a traditional corona, the first line of the first

poem serves as the final line of the last poem—and here, lines

hinging upon the word "look" both open and close the entire

sequence.

But these repeated bits are

only words, and not entire lines, a stickler might argue. As mastery

increases, I would respond, so too does the poet's understanding of how

to spin tradition and manipulate form. Consider the Elizabethan

poets' 12-line sonnets; George Meredith's 16-line sonnets; Rainer

Maria Rilke's love sonnets (written, in colloquial language, not about

the dark lady or the innocent girl—but about dogs and mirrors and the

beloved act of breathing itself); Wanda Coleman's explosive American sonnets.

These revolutionary responses to poetic predecessors represent what

some consider the apotheosis of the sonnet form: classics made modern,

thereby keeping the form alive.

Honorable

Mentions: Tom Howard Prize

"Water"

by Sylvia Adams

This poem is full of deep imagery linking the physical and spiritual

realms. As the living are rescued, panicked, from the trees and

rooftops they cling to, the dead find respite in "Water". The

living are saddened by the sight of homes lifted from their very

foundations, contents spilled. Yet the dead discover comfort in the

sensation of being unmoored. Even as the living attempt to dredge the

depths—always keeping an eye on the forecast, in fear of another

storm—the dead find quietude. And as material objects tangle and catch,

rendered useless, the dead hum while they float. They are caressed and

recognized. Respected. Not quite gone for good.

"Shorn"

by Katie Bickham

Rhythmic and emotional as a hymn, but stripped of its faith and

adornment, this poem stands before us naked, pleading, incriminating.

"Shorn", a truly meticulous rant, embodies the unique quality

that Wordsworth used to define poetry: it "...takes its origin

from emotion recollected in tranquility." It seethes. It

envisions. It assesses. It alludes. And in the end, this poem doesn't

even let God off the hook.

"My

Brother In Law Leaves the World" by Richard Brook

The word "meaning" stems most recently from an Old English

verb. Mænan is to mean: to intend or signify. But it is

also to tell—to lament. And "My Brother In Law Leaves the

World" is an elegiac poem, but also a meticulous piece of carpentry

that turns meaning into a hinge, metaphor into a joist. The precision

of its language is unequivocal, the cohesion of its imagery

breathtaking. A man tracks the histories, the legacies of words from

East to West. Afternoon sunlight whitens a desk. And finally a

dictionary lies open, wings spread, as birds lose their names and the

spirit itself prepares to fly.

"Celestial

Bodies" by Rata Gordon

This poem is an ultra-compact galaxy of facts, impressions, and images

bound by gravitational attraction. Each word, stanza, section that

comprises it is both whole and part—and occasionally its center (the

magnetic relationship between "me" and "you")

generates vivid flares: "I don't like it / when you fall asleep /

on top of me." Perhaps, like our own galaxy, "Celestial

Bodies" is on a collision course.

"Belonging"

by Atoosa Grey

How is it that, not knowing the name of the city in

"Belonging", I'm certain I've been there? How is it I've seen

its orange light bending like a whale; felt its wind following my

running form? How is it that I have been both the daughter and the

mother in this exquisite poem, which holds the reader close—breathing

when we breathe, turning when we turn, sighing as we sigh too?

"A

Short Bibliography of Secrets" by Mary O'Melveny

O'Melveny makes intimate reference to the stories shaping three

generations' lives—identifying each subject and period; giving credit,

sought or unsought, to the authors of major incidents. Like any

bibliography worth consulting, this structured record provides critical

notes leading to more: discoveries of misplaced faith and kindness;

traumas rising from the depths of memory; reflections on the cowardice

and wisdom of running away; and stupefying realizations like the fact

that people leave, sometimes, without leaving, or that our lives are

both larger and smaller than we know.

"Seeing

Through Glass" by Michelle Tibbetts

This is one of the most unique poems I've read this year. Deceptively

straightforward, it offers a literary lens for viewing the parent-child

relationship. What merits a child's selfish love but the assurance of

being seen, valued, saved? And what is the reward of bearing offspring

if not perceiving the world anew? In fascinating symbolic imagery, the

poet answers these questions and others.

Honorable

Mentions: Margaret Reid Prize

"Aletha"

by Trent Busch

"Aletha" was the first contest entry to haunt me. I moved past

it, then circled back, as the poem inevitably circles back to memories

of demure Aletha: etymologically, and in urban parlance, a powerful

speaker of truth. Throughout many long nights of reading, I never quite

shook this poem. Instead, its loose ballad rhythm and dark pastoral

imagery shook me. Is it Time, or another speaker, whose advances Aletha

chastened? No matter: both will be finished in the gloaming.

"Estate

Sale" by Teri Foltz

The sestina is a complicated, unforgiving form. Appropriate, then, that

"Estate Sale"—a complex, unflinching poem—should adopt this

structure. Here, the living brush aside or cannibalize the dead. Here,

intentions fray and tradition tires. Nobody will read the obituary.

Nobody—not even the earth—will make drastic accommodations. The entire

world is frozen solid, but for the scalding words that recur from

opening to envoi, changing forms so nimbly that one barely recalls

having met them in their former incarnations.

"Sonnet

for the Driveways of Our Childish Years" by Curtis

LeBlanc

Missed/violence. Lawn/down. Dishing/eclipsing. Mothers/other.

Forced/outdoors. Palms/alone. Read this sonnet aloud, and you'll find

that its near-rhyme reveals its true rhythm, which is as natural as the

shhhh of your breath; the pound of your pulse. American as basketball,

universal as growing up, "Sonnet for the Driveways of Our Childish

Years" reflects a narrow slice of history but, in doing so,

divines an expansive swath of our national consciousness.

"The

Vultures of Mumbai" by Jeanne-Marie Osterman

This poem derives its hypnotic strength from a blend of formal

structural elements—including couplets, rhyme, a cadenced refrain and

other elements of the ghazal. Like a traditional ghazal, too, "The

Vultures of Mumbai" evokes metaphysical questions and melancholic,

symbolic visions. But unlike a ghazal (a form with seventh-century

Arabian roots that have branched to take hold worldwide, thanks to

literary heavyweights including Rumi, Hafiz, Goethe and García Lorca,

as well as popular singers like Jagjit Singh and Begum Akhtar), this

poem employs its own unique architecture. It disrupts the ghazal's

time-honored rhyme-refrain scheme, just as modern advancements disrupt

sacred traditions. Its surging cell towers and luxury towers expose and

indict the living, even as the Towers of Silence ritually expose the

dead.

"The

Following Shadow" by Kathleen Spivack

The French Canadian sonnet's volta, or turning point, occurs in its

rhymed ninth and tenth lines. Yet "The Following Shadow"

takes subtle turns throughout: birds conjugate the original Latin love

song as clouds dream and the sobs of somebody far away ring out with

the rhythm of the waves. It is only fitting, then, that the poem ends

with a clever homonym, sketching an elliptical moon directly above us—a

faint, abstruse oval that will flutter from sight even as we crane our

necks to track it.

"The

Insurgent" by Eliot Khalil Wilson

There is a curving river in Ghana that was named The Volta by

Portuguese gold traders, as its waters were where they reversed course

and headed home. Like the river, the poetic volta (or "turn")

in the final couplet of this modern Shakespearean sonnet represents a

shift in direction: a devastatingly final current that turns us around

and brings us swiftly home to the poem's central truth. But first, in

fluid iambic pentameter with just enough metrical variation, we travel.

We explore. For the quatrains of "The Insurgent" carry us

nimbly over expansive terrain, past barriers that are no obstacle, into

war and dreams of war, to witness protocols that fail and precautions

that kill.

|

No comments:

Post a Comment